Architecture is a discipline that combines and encompasses a wide variety of definitions. At its most basic level, it is understood to be the ‘the process of planning, designing and constructing buildings or structures.’

However, architecture is also a means of expression. It can be a political statement, a collaborative process, an art form a reflection of culture or a combination of any of these. It requires technical competency of a high level, embracing the sciences, as much as reflecting the arts. It is a human expression of form, as much as it is the creation of a structure giving shelter.

The practice of architectural design is used to meet both functional and artistic needs, therefore serving both practical and creative goals. It can be beautiful, enhancing the experience of the space, perhaps even inspirational or controversial. And in this respect, it is undoubtedly an artistic expression.

Not all buildings are architecturally designed of course. To choose an architect is to choose aesthetics over pure function and it can be argued that those structures that are designed and created by building contractors, or perhaps even by architectural technicians, result in the main in buildings lacking presence or personality.

We are naturally affected and inspired by the world around us and architecture, drawing inspiration from so many other disciplines, is inevitably a source of inspiration in itself. It seems odd then that so few architect-designed buildings around the world are signed by their creators. A signature or an artist’s mark to claim and identify their work as genuinely their own, is intrinsic to so many other art and craft forms. And identifying one’s work, one’s input is not limited to purely fine art forms. Photographers, authors, actors, directors, choreographers, journalists, musicians are all credited wherever their work is seen, heard, or printed. So why not architects?

One might reason that, unlike many other art forms, the creation of a building involves a whole team of people to realise it. But then so do other art forms. The creation of bronze sculptures, for example, requires not only the artist’s conceptualisation and their original designs, but a foundry and experts in casting bronze. Sculptures in stone require the stone to be hewn out of the rockface in a certain way. The stone needs to be handled, shipped, and prepared, all by others involved in the creation at some level. Many famous artists quite acceptably run studios or ateliers too, with technicians and apprentices involved in creations conceptualised by the master artist or crafts person.

Architects must learn how to design, but crucially their designs have purpose. Understanding the requirements and desires of a client is only the beginning. Architects must be conversant in problem solving so that the clients’ brief can be interpreted into a successful, constructable building. To achieve this, they must understand the science of building technologies, have a thorough grasp of the construction process, and keep up to date with new advances in sustainable building solutions.

Architecture is a very important part of our lives. It affects the way we live, work, and play. Good architecture can make us feel happy, comfortable, and safe. Bad architecture can have the opposite effect.

Buildings designed by architects could be perceived to be structural artworks. They can act as cultural emblems, as contemporary and historic markers, and as technically competent and aesthetically beautiful structures to live and work in.

Perhaps architecture can be acknowledged as an art form but does not fit into the category of ‘fine art’ because of the very fact that it also serves a valuable purpose. Architects’ main area of skill and expertise is in maximising design opportunities for the client, the site, and the budget. And in this last lies an anomaly. We accept that civic buildings might be marked in some way by those that paid for it, often with an inscribed foundation stone or a plaque inside the building. Or, if you are Donald Trump, with your name all over the exterior of the building. This is akin to, say, commissioners of art having their own signatures on the artworks they collect.

Similarly, there are many examples of buildings all around the world that are named after famous or locally well-known people. Except for a handful of royal personages, inevitably history has assigned most of these to men, though this is gradually changing. There are, however, but a handful of buildings named after the architects that devised them and guided their construction through the whole process.

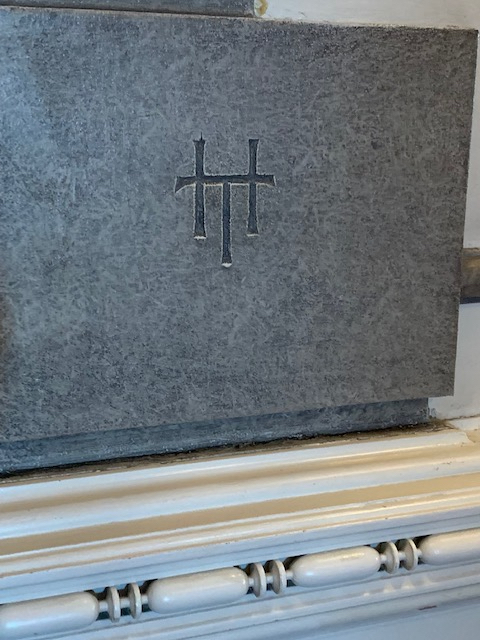

Quirkily, Christiansborg Royal Palace in Copenhagen, originally intended both as a residence for the Royal Family and the headquarters of the Danish Parliament, flaunts upon several of its walls the initials of Hans Christian Harald Tegner (HT), the interior designer commissioned on the third reconstruction of the palace in the early 1900’s. But once again, no marks, signs, or commemorative plaques acknowledging the principal architect, Thorvald Jørgensen nor either of the architects before him.

Chicago is one of the very few places in the world to honour the creator of their buildings. The Hotel Burnham (constructed 1895) acknowledged its architect Daniel Burnham until it was renamed in 2016, the Sullivan Center is named for the architect Louis Sullivan (1856-1924) and more recently the prolific but little-remembered Chicago architect Edward H. Bennett (1874-1954), has been honoured in Chicago’s 843-foot apartment and condo tower at 451 E. Grand Avenue, now “One Bennett Park.“

A search for buildings in the UK named after their architects, or even signed by their architects reveals just one. Newcastle University have named their new centre for architecture, due to open in April 2023, The Farrell Centre, after renowned architect Sir Terry Farrell. The irony here is in the fact that although Sir Farrell donated £1m to the project, along with his own architectural archive of architecture related material, the architects of this building are in fact Space Architects and Elliott Architects working in close collaboration with Farrell Centre director, Owen Hopkins.

That is not to suggest that all public architect-designed buildings should be named after them: the intrinsic allocation of a mark or a signature would be enough. But it seems that even when an architect is behind the funding of a building, the original designers and creators continue to be denied credit where recognition is due.